The Formative Decade of Ernest Hemingway: A Look at His Writing Journey from 1920-1929

Share

Ernest Hemingway is a literary titan, renowned for his terse prose and profound impact on 20th-century literature. The 1920s were a pivotal decade in his career, shaping his distinctive style and setting the stage for his lasting legacy. This post delves into Hemingway’s writing journey during this formative period, exploring the experiences and works that defined his early career.

The Early 1920s: Beginnings and Breakthroughs

Hemingway’s literary journey in the 1920s began in the bustling streets of Paris, a city teeming with creative energy and intellectual vibrancy. As an expatriate writer, he immersed himself in the city’s artistic community, drawing inspiration from fellow writers like Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and James Joyce.

Journalism and First Publications

In 1920, Hemingway was honing his craft as a journalist for the Toronto Star. This experience was instrumental in developing his concise, impactful writing style. His journalistic work required him to convey information clearly and succinctly, a skill that would later characterize his fiction.

His first foray into fiction came with the publication of “Three Stories and Ten Poems” in 1923. This collection showcased his emerging voice, blending stark realism with emotional depth. It was a modest beginning, but it marked Hemingway’s entry into the literary world.

The Mid-1920s: Defining His Style

The mid-1920s were transformative for Hemingway. During this period, he published several works that solidified his reputation as a significant literary figure.

“In Our Time” (1925)

“In Our Time,” published in 1925, was a breakthrough. This collection of short stories and vignettes demonstrated Hemingway’s mastery of the minimalist style. Each story, with its spare prose and underlying tension, illustrated his ability to convey profound meaning with economy of words. “In Our Time” introduced readers to Hemingway’s thematic concerns—war, love, loss, and the human condition.

“The Sun Also Rises” (1926)

Hemingway’s first novel, “The Sun Also Rises,” followed in 1926. Drawing from his own experiences in Europe, the novel depicted the post-World War I expatriate community. The novel’s protagonist, Jake Barnes, embodied the disillusionment and aimlessness of the “Lost Generation.” The book’s innovative structure and Hemingway’s distinctive style received widespread acclaim, cementing his status as a leading voice in modern literature.

The Late 1920s: Maturity and Mastery

As the decade progressed, Hemingway continued to refine his craft, producing works that would further establish his literary legacy.

“Men Without Women” (1927)

In 1927, Hemingway published “Men Without Women,” a collection of short stories that delved into themes of masculinity, isolation, and existential struggle. Stories like “The Killers” and “Hills Like White Elephants” are prime examples of Hemingway’s “iceberg theory”—a writing technique where the underlying themes and emotions are implied rather than explicitly stated.

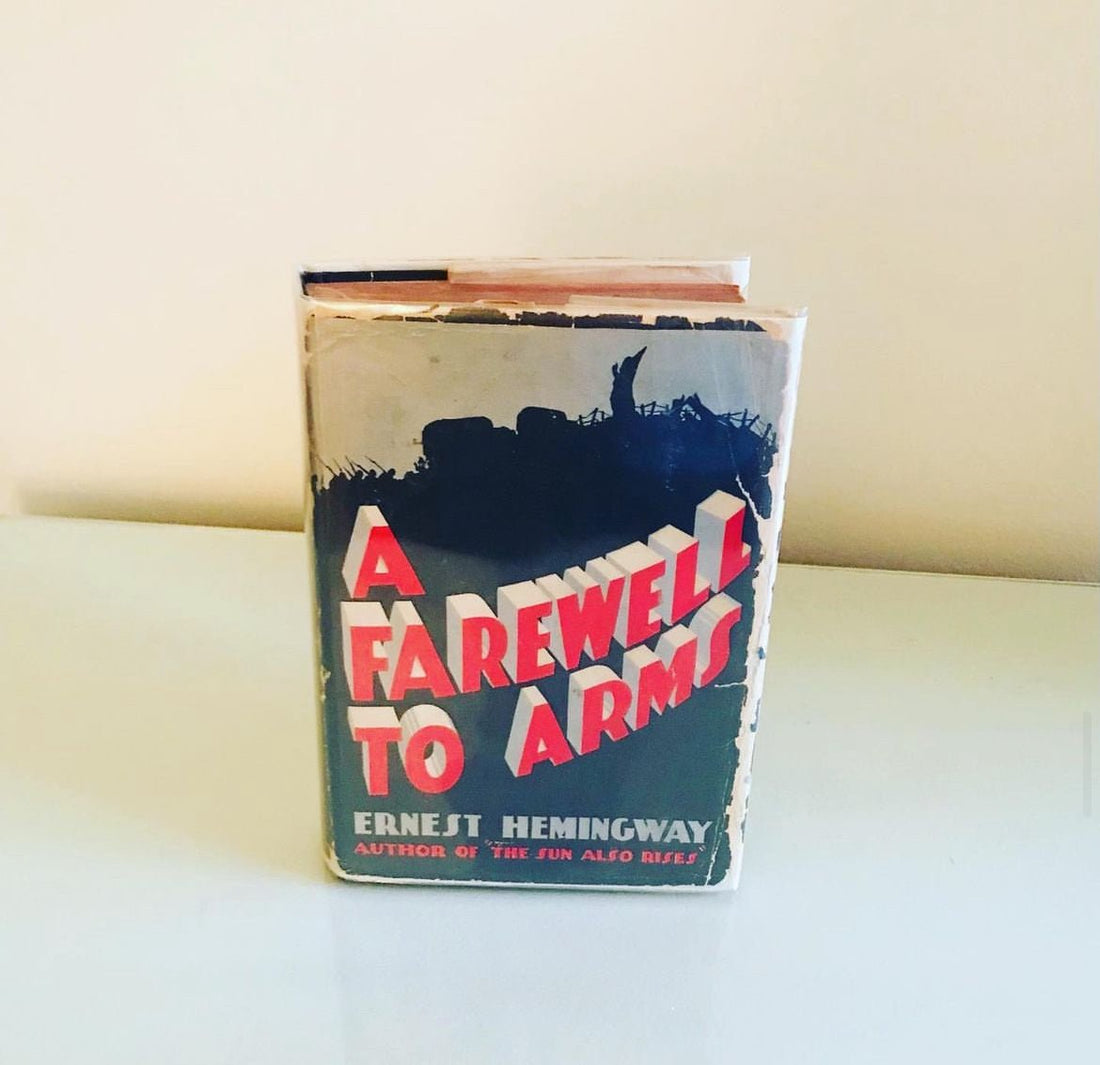

“A Farewell to Arms” (1929)

The decade culminated with the publication of “A Farewell to Arms” in 1929. This novel, set against the backdrop of World War I, is a poignant exploration of love and loss. The protagonist, Lieutenant Frederic Henry, mirrors Hemingway’s own wartime experiences, infusing the narrative with authenticity and emotional depth. “A Farewell to Arms” was both a critical and commercial success, further solidifying Hemingway’s place in the literary canon.

Hemingway’s Enduring Legacy

The 1920s were more than just a decade of productivity for Hemingway; they were the years that defined his voice and solidified his literary reputation. His experiences as a journalist, his interactions with the expatriate community in Paris, and his personal encounters with love and war all contributed to the unique style and thematic depth of his work.

Hemingway’s writings from this decade continue to resonate with readers and writers alike. His ability to convey complex emotions with simplicity and precision has influenced countless authors and remains a benchmark for literary excellence. As we look back on Hemingway’s early career, it’s clear that the 1920s were not just a beginning but a bold declaration of a new literary era.

In revisiting Hemingway’s journey through the 1920s, we gain insight into the makings of a literary giant whose works continue to captivate and inspire generations.

References

1. “Ernest Hemingway.” Biography, https://www.biography.com/writer/ernest-hemingway.

2. “Ernest Hemingway: Biography, Works, and Style.” Study.com, https://study.com/academy/lesson/ernest-hemingway-biography-works-and-style.html.

3. Meyers, Jeffrey. “Hemingway: A Biography.” Da Capo Press, 1999.

4. “Three Stories and Ten Poems.” Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum, https://www.hemingway.astate.edu/three-stories-and-ten-poems.

5. “In Our Time.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/In-Our-Time-by-Hemingway.

6. “In Our Time: Overview and Themes.” CliffsNotes, https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/h/hemingways-short-stories/summary-and-analysis/in-our-time.

7. “The Sun Also Rises: Hemingway’s Masterpiece.” The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1926/10/23/the-sun-also-rises.

8. “The Sun Also Rises: Themes and Analysis.” SparkNotes, https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/sun.

9. “Men Without Women: Analysis of Hemingway’s Short Stories.” GradesFixer, https://gradesfixer.com/free-essay-examples/analysis-of-ernest-hemingways-short-story-men-without-women.

10. “Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory.” Literary Devices, https://literarydevices.net/iceberg-theory.

11. “A Farewell to Arms: Summary, Characters, and Themes.” LitCharts, https://www.litcharts.com/lit/a-farewell-to-arms.

12. “A Farewell to Arms: Hemingway’s War Story.” NPR, https://www.npr.org/2012/07/11/156620805/hemingways-a-farewell-to-arms-gets-a-lifesaving-review.

13. Baker, Carlos. “Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story.” Scribner, 1969.

14. “Hemingway and the Lost Generation.” History.com, https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/lost-generation.

The Early 1920s: Beginnings and Breakthroughs

Hemingway’s literary journey in the 1920s began in the bustling streets of Paris, a city teeming with creative energy and intellectual vibrancy. As an expatriate writer, he immersed himself in the city’s artistic community, drawing inspiration from fellow writers like Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and James Joyce.

Journalism and First Publications

In 1920, Hemingway was honing his craft as a journalist for the Toronto Star. This experience was instrumental in developing his concise, impactful writing style. His journalistic work required him to convey information clearly and succinctly, a skill that would later characterize his fiction.

His first foray into fiction came with the publication of “Three Stories and Ten Poems” in 1923. This collection showcased his emerging voice, blending stark realism with emotional depth. It was a modest beginning, but it marked Hemingway’s entry into the literary world.

The Mid-1920s: Defining His Style

The mid-1920s were transformative for Hemingway. During this period, he published several works that solidified his reputation as a significant literary figure.

“In Our Time” (1925)

“In Our Time,” published in 1925, was a breakthrough. This collection of short stories and vignettes demonstrated Hemingway’s mastery of the minimalist style. Each story, with its spare prose and underlying tension, illustrated his ability to convey profound meaning with economy of words. “In Our Time” introduced readers to Hemingway’s thematic concerns—war, love, loss, and the human condition.

“The Sun Also Rises” (1926)

Hemingway’s first novel, “The Sun Also Rises,” followed in 1926. Drawing from his own experiences in Europe, the novel depicted the post-World War I expatriate community. The novel’s protagonist, Jake Barnes, embodied the disillusionment and aimlessness of the “Lost Generation.” The book’s innovative structure and Hemingway’s distinctive style received widespread acclaim, cementing his status as a leading voice in modern literature.

The Late 1920s: Maturity and Mastery

As the decade progressed, Hemingway continued to refine his craft, producing works that would further establish his literary legacy.

“Men Without Women” (1927)

In 1927, Hemingway published “Men Without Women,” a collection of short stories that delved into themes of masculinity, isolation, and existential struggle. Stories like “The Killers” and “Hills Like White Elephants” are prime examples of Hemingway’s “iceberg theory”—a writing technique where the underlying themes and emotions are implied rather than explicitly stated.

“A Farewell to Arms” (1929)

The decade culminated with the publication of “A Farewell to Arms” in 1929. This novel, set against the backdrop of World War I, is a poignant exploration of love and loss. The protagonist, Lieutenant Frederic Henry, mirrors Hemingway’s own wartime experiences, infusing the narrative with authenticity and emotional depth. “A Farewell to Arms” was both a critical and commercial success, further solidifying Hemingway’s place in the literary canon.

Hemingway’s Enduring Legacy

The 1920s were more than just a decade of productivity for Hemingway; they were the years that defined his voice and solidified his literary reputation. His experiences as a journalist, his interactions with the expatriate community in Paris, and his personal encounters with love and war all contributed to the unique style and thematic depth of his work.

Hemingway’s writings from this decade continue to resonate with readers and writers alike. His ability to convey complex emotions with simplicity and precision has influenced countless authors and remains a benchmark for literary excellence. As we look back on Hemingway’s early career, it’s clear that the 1920s were not just a beginning but a bold declaration of a new literary era.

In revisiting Hemingway’s journey through the 1920s, we gain insight into the makings of a literary giant whose works continue to captivate and inspire generations.

References

1. “Ernest Hemingway.” Biography, https://www.biography.com/writer/ernest-hemingway.

2. “Ernest Hemingway: Biography, Works, and Style.” Study.com, https://study.com/academy/lesson/ernest-hemingway-biography-works-and-style.html.

3. Meyers, Jeffrey. “Hemingway: A Biography.” Da Capo Press, 1999.

4. “Three Stories and Ten Poems.” Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum, https://www.hemingway.astate.edu/three-stories-and-ten-poems.

5. “In Our Time.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/In-Our-Time-by-Hemingway.

6. “In Our Time: Overview and Themes.” CliffsNotes, https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/h/hemingways-short-stories/summary-and-analysis/in-our-time.

7. “The Sun Also Rises: Hemingway’s Masterpiece.” The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1926/10/23/the-sun-also-rises.

8. “The Sun Also Rises: Themes and Analysis.” SparkNotes, https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/sun.

9. “Men Without Women: Analysis of Hemingway’s Short Stories.” GradesFixer, https://gradesfixer.com/free-essay-examples/analysis-of-ernest-hemingways-short-story-men-without-women.

10. “Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory.” Literary Devices, https://literarydevices.net/iceberg-theory.

11. “A Farewell to Arms: Summary, Characters, and Themes.” LitCharts, https://www.litcharts.com/lit/a-farewell-to-arms.

12. “A Farewell to Arms: Hemingway’s War Story.” NPR, https://www.npr.org/2012/07/11/156620805/hemingways-a-farewell-to-arms-gets-a-lifesaving-review.

13. Baker, Carlos. “Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story.” Scribner, 1969.

14. “Hemingway and the Lost Generation.” History.com, https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/lost-generation.